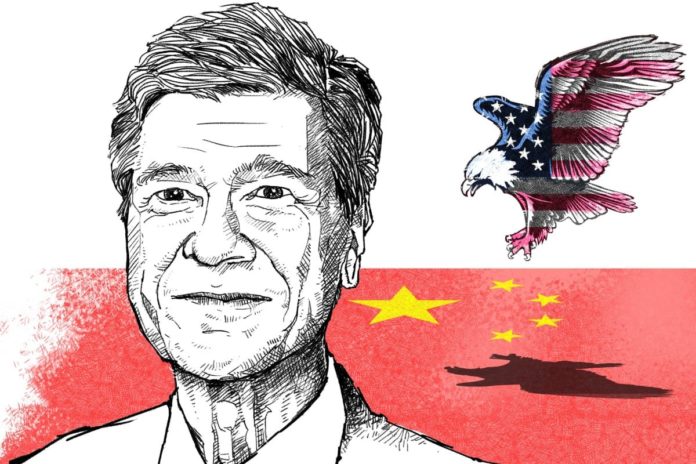

American economist Jeffrey Sachs on the US deep state’s reaction to China’s success, and why we’re not seeing the end of globalization

Jeffrey Sachs is an economics professor and director of the Centre for Sustainable Development at Columbia University. This interview first appeared in SCMP Plus.

You were part of a high-level US business and academic delegation to China in March. What are your thoughts about the trip and the meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping? What has been achieved and what has yet to be done?

The China Development Forum was an excellent opportunity, as usual, for an update on China’s economy and foreign policy outlook. Chinese leaders have a very realistic view of the domestic and also the global situation, notably regarding the tensions with the US.

In my own view, the US-China tensions are overwhelmingly caused by the American anxiety that US power is waning around the world. US policymakers are reacting defensively and fearfully, and often very unwisely.

I wonder if you could elaborate more about the unwise China policies made by the US? Can you give us some examples, and why were they unwise?

The US launched a policy around 2015 to “contain” China, including several components. These policies – spelled out in a 2015 article for the Council on Foreign Relations by Robert Blackwill and Ashley Tellis – included the attempt to create trade agreements, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) designed to exclude China, increased export bans on hi-tech products such as advanced semiconductors, increased trade barriers to China’s exports to the US (and Europe), increased militarisation of the South China Sea, new military alignments such as Aukus, and opposition to Chinese initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative.

I believe that every one of these approaches is a failure. They do not “contain” China, but they raise tensions, lower economic well-being and global economic efficiency, divide the world economy, and bring us close to war.

What is your assessment about China’s economic development in the next five years? China has recently launched a campaign to upgrade its industries in order to spur its economy – do you think it will work?

China is already at the cutting edge of many of the key global technologies needed for the coming 25 years: photovoltaics, wind power, modular nuclear power, long-distance power transmission, 5G (now 5.5G), batteries, electric vehicles and other areas. These will keep the Chinese economy moving forward.

The US and Europe are turning protectionist, so China’s markets will increasingly be in Asia, Russia, the Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America.

The Belt and Road Initiative and related policies will play a larger role as the world invests in the new energy and digital systems. China’s trade and financial relations will turn increasingly towards the emerging and developing countries. It’s notable that the Brics are already significantly larger in GDP than the G7. Of course, the best outcome economically would be a globally connected and integrated world.

Along the line of China’s industrial upgrade, do you think there will be overcapacity in the EV sector? Will the EV sector become a major point of contention between China, the US and the EU?

There is no overcapacity in EVs, but there is the need to build out EV markets in the emerging and developing countries. Unfortunately, the US and Europe are likely to become more protectionist and will significantly close their markets to China’s EVs, but the US and European EV producers will not be able to compete with China’s EVs in third markets in the emerging and developing economies.

In a recent newsletter of yours, you said US primacy is no longer possible given the US share of world output is smaller than China’s: 14.8 per cent for the US and 18.5 per cent for China. Why is China’s primacy not possible? Also, can Brics challenge the G7 to become the most powerful economic bloc given its production output is 35.2 per cent – higher than the G7’s 29.3 per cent?

Most likely, no country will be hegemon in the 21st century because technological and military capacities will be too widely spread, and demographic trends will weigh against a single hegemon. The US, EU, China, India, West Asia, African Union and South America (led mainly by Brazil), will each have their place and role regionally, without a global hegemon. China in particular will continue to raise income levels per person. But with an absolute decline in population, China’s share of world output will most likely not increase beyond 20 per cent (measured at PPP).

China’s population is likely to fall from around 18 per cent of the world population today to perhaps 10 per cent of the world population in 2100. Nothing is bad or wrong with that, from China’s perspective, in terms of well-being and security. Yet it will mean that China’s share of world output will be limited by demographic trends.

Let us add that there is no history of China even attempting to become a global hegemon. China’s long history of statecraft was not based on obtaining overseas empires. I find it notable, for example, that China never once tried to invade Japan during more than 2,000 years of statecraft, except during the short period when the Mongols ruled China, and the Mongols tried unsuccessfully twice to invade Japan – in 1274 and 1281.

On the diplomatic front, how is the US election result going to affect US-China relations? Some analysts say that if Biden wins bilateral relations will be more predictable, while Trump tends to be more unpredictable and he may launch a trade war with China. What is your view?

Relations will be difficult no matter who is elected president in November. The US “deep state” has so far been unable to accept the reality of China’s success. The US deep state still operates according to the delusions of US “primacy” which no longer exists (and US primacy was limited even 30 years ago). This is a dangerous delusion, as it could lead to a US-China war in Asia, as it has led to a US-Russia proxy war in Ukraine.

Can you explain to our readers what is the “deep state” in the US and what do you think is their agenda? Some people have dismissed the notion of deep state as a conspiracy theory – what is your comment on that?

The deep state is the set of US security institutions, including the White House (and the president’s National Security Council), the Pentagon, the intelligence agencies (centred on the CIA), the Armed Services Committee and Foreign Affairs Committee of Congress, and the major arms contractors (notably Lockheed Martin, RTX, Boeing, General Dynamics and Northrop Grumman). They are the drivers of America’s wars, regime-change operations, and foreign policy more generally. This is a big business, involving more than US$1 trillion dollar per year in direct outlays, so there is heavy lobbying involved as well.

This is not any kind of conspiracy theory, just a fact about the organisation of the US state. There is little role of public opinion involved in US security policy (including wars and regime-change operations). Much of it is indeed secretive, which is why whistle-blowing and leaks are considered such a high offence in the US. The deep state has been engaged in perhaps 90 covert and overt regime-change operations since 1947 (the date the CIA was created), and in pervasive warfare. The deep state manages a network of more than 750 overseas military bases in around 80 countries, and those bases of operation are key to US-led wars and regime-change operations.

Beijing and Western countries have been accusing each other of conducting covert operations to destabilise the other side. How much of this do you think is conspiracy theories, and how much is real?

US foreign policy is based on military alliances, economic pressures, and covert operations of destabilisation. This is all well documented, and applies to China, Russia and other regions of the world. US actions in East Asia (military bases, military alliances, trade measures, covert operations) are indeed designed to contain or weaken China. US actions vis-à-vis Taiwan, especially continuing to arm Taiwan contrary to the letter and spirit of the August 17, 1982 US-PRC Communique, are the most dangerous and destabilising of the US actions.

It is worth recalling key language of that communique: “The United States government states that it does not seek to carry out a long-term policy of arms sales to Taiwan, that its arms sales to Taiwan will not exceed, either in qualitative or in quantitative terms, the level of those supplied in recent years since the establishment of diplomatic relations between the United States and China, and that it intends gradually to reduce its sale of arms to Taiwan, leading, over a period of time, to a final resolution.”

That was 42 years ago.

Can you elaborate on why containment of China might lead to war? Do you mean there may be miscalculations in the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea that may trigger military conflicts? Also, in your recent commentaries you have warned about the risks of a nuclear war. What role can China play to reduce such risks?

In the US media, there is a recent flood of talk about war with China. This is horrendously irresponsible, ignorant and dangerous. Such a war would be devastating and must be avoided at all cost. Even the casual discussion of such a possibility betrays a lack of prudence and judgment. The US should stop meddling in the Taiwan issue.

Without US meddling, it will be handled peacefully by both sides. With US meddling, the danger of conflict is much higher. This is the kind of miscalculation that led to the disastrous war in Ukraine. The US wanted to push Nato to Ukraine and thought it could get away with it despite Russia’s firm red line against it. The US completely misjudged, and the war ensued. Then the US thought that Ukraine could defeat Russia on the basis of Nato arms and Western sanctions. This too was a profound misjudgment. The consequences for Ukraine have been devastating. My point is that the US security-state policymaking is not very sound or strong. Just look at the legacy of US-led wars of choice in Vietnam, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya and Ukraine, among other places.

You have been very outspoken in criticising the current US policies on handling China, Russia and other global issues. Do you think there is still quality debate about China and US relations? Some analysts say they can be attacked if they make comments perceived as being positive about China or not aligning with the mainstream narrative. How bad is the situation? Is it getting better or worse?

The level of foolishness in the US discourse is very high. That’s true in the media, but also in the think tanks sponsored by the military-industrial complex. The talk of war has become normalised.

Both Trump and Biden compete to show how tough they are vis-à-vis China, and much or most of the US Congress is even more absurd, because few members of Congress know much if anything about China, it’s history and its policies. These China-bashers resort to vulgar and dangerous anti-China rhetoric.

Twenty years ago, many believed that the Washington Consensus was the answer to eliminating poverty and helping the developing world. Now, many have lost faith in that and some have even turned to the China model. Do you think there is a third way? What lessons can we draw from the past 20 years?

There was and is a lot of convenient naivete in the US economic discourse. In promoting the Washington Consensus, the US government wanted to open the markets of other countries in order to control natural resources, establish financial institutions, and generally open the way for US foreign investments.

The promoters of the Washington Consensus didn’t pay much if any attention to issues such as education, healthcare, social protection, infrastructure, technology, research and development, environmental management, and the countless policy areas where the public sector has a major role, if not dominant role.

It was obvious to many of us 30 years ago that the Washington Consensus was full of empty rhetoric, not reality. This was obvious since most high-income economies themselves generally had government outlays of 40 per cent or more of GDP, which was completely inconsistent with the talk of “free markets” emanating from Washington.

Some people say we are now seeing the end of globalisation and the beginning of the fragmentation of the world economy. What is your comment on that? Are we entering into a new cold war and if yes, how does this one differ from the last one?

We are not seeing the end of globalisation. Globalisation has been part and parcel of human history and will remain so, especially as the new digital technologies make global linkages even more immediate. Overall, global linkages in trade, finance, technology, culture, travel, migration, science and technology are all here to stay. So too are the global linkages related to common global challenges such as human-induced climate change.

Yet we are also seeing increased protectionism in the US and Europe as they react defensively to the rise of China, Russia, India and other emerging economies. We are definitely seeing increased geopolitical tensions as well, mainly as the US again confronts the harsh reality that it is not in charge of the world. Alas, Biden still believes the US leads a unipolar world, and this delusion is the source of growing conflict.

You have commented extensively on the Ukraine and Gaza crisis – is there any role China can play to ease the tension in these cases? How big is the risk for a major escalation of the tension?

Both wars could end tomorrow through diplomacy. The Ukraine war was caused by the US push since the 1990s to enlarge Nato to Ukraine and Georgia with the goal of surrounding Russia in the Black Sea, an idea that goes back to Lord Palmerston in the 1850s and that was revived by Brzezinski in the 1990s.

This idea crossed Russia’s red line, quite understandably, since Russia rejects a US military alliance on its 2,100km border with Ukraine just as the US would absolutely reject a Russian or China military alliance with Mexico along the US border. This is all obvious, even if it is denied daily by the US government.

By finally recognising the futility and danger of trying to push Nato to Ukraine and Georgia, the US could take away the underlying cause of the Ukraine war.

The war in Gaza could also be ended tomorrow if the UN would recognise Palestine as the 194th UN member state along the lines of the 1967 border. The US is the only practical obstacle to this solution. Israel’s right-wing government utterly rejects a state of Palestine and counts on the US to back up Israel. Yet the whole rest of the world sees that the path to peace is through the two-state solution.

One can say that the growing dangers over Taiwan are similar. The US is unilaterally arming Taiwan despite the strenuous objections of the PRC. The US actions are in fact putting Taiwan in great peril, just as the US put Ukraine in great peril. The US should act with moderation and circumspection, and support peace not by arming Taiwan but calling for peaceful approaches across the strait. Diplomacy, not war, is the only viable approach.

China’s main role should be to promote diplomatic solutions in Ukraine and Gaza through the United Nations and based on the UN Charter. There should be a global UN conference on peace in Ukraine based on Ukraine’s neutrality; the end of the US attempt to expand Nato to Ukraine; and an end to the fighting. Unfortunately, the [June] “peace conference” in Switzerland (which was not a UN conference) was not based on such obvious steps.

There should also be a global UN conference to implement the two-state solution in Israel and Palestine. China and Brazil have reportedly discussed together the promotion of such a peace conference, and now the Arab League nations are calling for such a UN-backed conference.

The current trajectory, alas, is one of escalating war, mainly because the US government has forgotten about diplomacy with the other major powers. This is very dangerous. It’s urgently time to return to diplomacy.

Source: SCMP