In this eye-opening research paper, Dr. Mohammad Zahidul Islam Khan, a retired Group Captain of the Bangladesh Air Force, raises serious questions about the Indian role in the creation of Bangladesh. While Bengalis took credit of liberation, the Indians projected the event as a victory over Pakistan, and hence no senior Bengali army officer was invited to the ceremony where the surrender was signed.

A Seemingly Intuitive Question?

On the 54th Victory Day of Bangladesh, the Indian Prime Minister in his official X handle (formerly Twitter) posted: “Today we honor the courage and sacrifices of the brave soldiers who contributed to India’s historic victory in 1971.” 1 Modiji’s message, seemingly undermining Bangladesh’s ownership of the 1971 Liberation War raised an intuitive question: whose victory was it anyway?

The Bangladeshi polity reacted sharply. Ordinary citizens, politicians, and government executives condemned the Indian Prime Minister’s misleading recollection of history and distortion of the truth, further fueling the strained bilateral relationship after the fall of the Sheikh Hasina government in August 2024 and her subsequent asylum in India.

Amidst the flurry of emotive reactions to Modiji’s Vijay Diwas message, Bangladesh’s Ministry of The Foreign Affairs (MOFA) response stands out as an evidence-based reminder of the historical truth of 16 December 1971—the day on which the Pakistani troops surrendered at Dhaka, marking the victory of Bangladesh’s nine-month-long liberation struggle.

Quoting J. N. Dixit – former Indian Foreign Secretary, diplomat and National Security Adviser – the MOFA in its social media account posted: “A major political mistake at the surrender ceremony [of Pakistani forces at Dhaka on 16 December 1971] was the Indian military high command’s failure to ensure the presence of General M.A.G. Osmani, Commander from the Bangladesh side on the Joint Command…This was an unfortunate aberration that India could have avoided. The event generated much resentment among Bangladeshi political circles.”

Modiji’s Vijay Diwas message seems to repeat a similar mistake adding to the historic resentment of Bangladeshi polity against India. Indeed, the seemingly trivial and intuitive question: ‘whose war was it anyway’, appears to be staid but ineluctable. The answer to this question lies in the geopolitical dimension of the Liberation War.

Liberation War to Internationalized Civil War

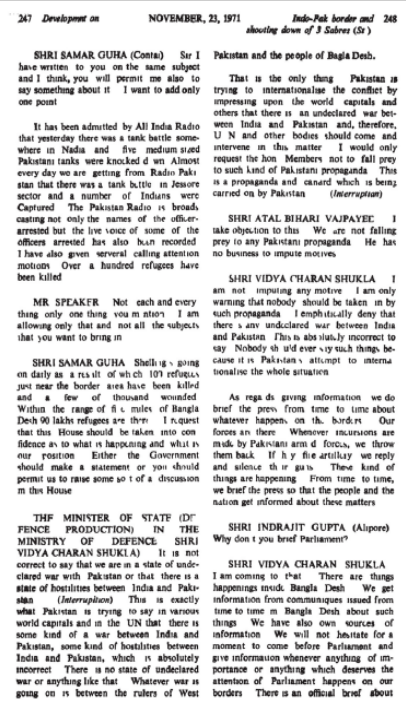

Most historians maintain that the coordinated offensive of 21st November 1971 – celebrated as Armed Forces Day in Bangladesh – marked India’s first overt military intervention in support of Bangladesh’s ongoing Liberation War. The November offensive transformed

our Liberation War into an internationalized civil war. Bangladesh intensified her fight following the coordinated offensive. But India took a strange pause till 3rd December, relegating her overt military action in the East as an ‘insignificant prelude’ initiated by a ‘local commander.’4 Much to the dismay and frustration of the Bangladeshi crews, the planned D-Day of Kilo Flight – the embryo of today’s Bangladesh Air Force – to launch

their first air attack inside East Pakistan on 28 November was also postponed until 3rd December by the Indian High Command.

Downplaying the overt military offensive in the East, the Indian Defence Minister, at the Lok Sobha, stressed that India is not in a “state of hostilities” with Pakistan, adding that Pakistan is trying to “internationalize” the War.6 General Osmani, Bangladesh’s Commander-in-Chief, also noted that the Indian troops were not “cleared” to join the fight in the Eastern theatre until 3rd December to avert the international community’s growing demands for a ceasefire and deployment of United Nations observers.7 That said, the coordinated offensive rattled the Pakistani President, prompting him to declare a state of emergency and reach out to the UN Secretary-General, seeking his “personal” intervention to stave off a military defeat in the East.

These insular but reflective accounts shaped the extant literature and the global history of

Bangladesh’s 1971 Liberation War

Coding Bangladesh’s liberation struggle as an “interstate” war, the Harvard Dataverse – a global war dataset used by the researchers – records 20 November and 17 December as the start and end date of the war and lists India as the “initiator” of the War. The Correlates of War (COW) dataset – another widely used dataset – projects Pakistan as the “initiator”. Coding it as a “civil war over local issues” the COW intra-state war dataset records 25 March and 2 December as the start and end date while COW’s interstate war dataset lists 3 December 1971 as the start date of the ‘Indo-Pak war.10 Pakistan’s pre-emptive air strike in the West on 3 December exposed her as an ‘aggressor’

and ‘initiator’ transforming our Liberation War into an internationalized civil war, dubbed as the “Indo-Pak” war.

For Bangladesh, the November offensive was not a ‘prelude.’ It was a continuation of the ongoing fight leading to an inevitable merger of the two Forces. It exposed the Provisional Government of Bangladesh (hereafter PGB) to the full spectrum of complexities and challenges of managing an internationalized civil conflict and retaining the political authority and ownership of the War.

Authority and Ownership of an Internationalized Civil War

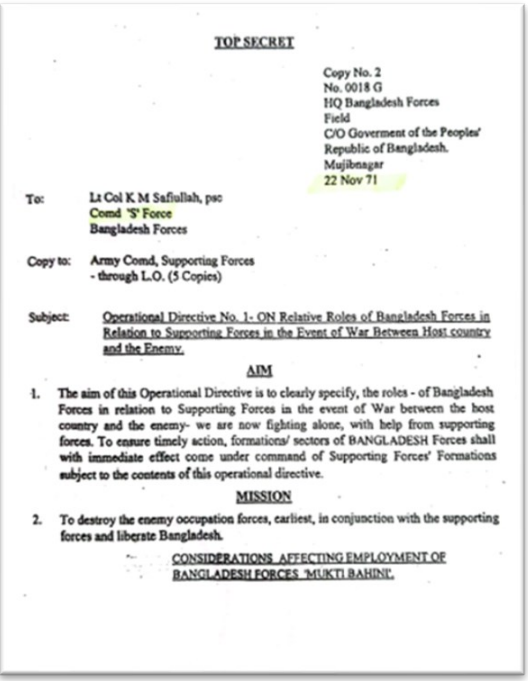

On 22nd November 1971, the PGB issued its first top secret Operational Directive defining the “Relative Roles of Bangladesh Forces in Relation to Supporting Forces [India] in the Event of War Between the Host Country [Bangladesh] and the Enemy [Pakistan].”12

The Directive, issued by Bangladesh’s Commander-in-chief (C-in-C), included instructions on command relationships, roles of “Supporting” Forces, allotment of troops, boundaries, logistics, and civil administration of liberated areas, etc. Bangladesh Formations/Sectors

were placed under the Supporting Forces’ command, requiring the Supporting Forces to “provide full logistic support”.

The unique Directive raises a few intuitive questions. Why did it specify Bangladesh as a “host” country which was yet to be recognized by any states including India? Why were the Indian troops called “Supporting Forces”? Why did the C-in-C agree to place Bangladeshi Forces under the command of “Supporting” forces in a somewhat unorthodox military practice? Answers to these questions illuminate our understanding of whose victory it was anyway.

First, geopolitics can fragment the political authority and ownership of internationalized civil war leading to unintended outcomes. In the context of Bangladesh, a perception prevailed that if India succeeds in helping to create Bangladesh, then “East Pakistan will become a Bhutan and West Pakistan will become a Nepal. And India with Soviet help would be free to turn its energies elsewhere.”

More than anyone, Tajuddin Ahmed – Bangladesh’s first Prime Minister, perhaps realized the complex motives of external actors and the necessity to retain the ownership of the War. In one of his wartime addresses to the nation, Ahmed stated: “Bengalis undoubtedly rely on their own power …but there is a satisfaction to be derived from the signs of support from quarters where before there was only caution.”

The predicament to retain ownership of the War, after India’s military involvement, was also echoed by Abdur Razzaq, a key figure of the “nucleus” of our freedom struggle. Reiterating Mukti Bahini’s pledge to fight a long-drawn war, Razzaq noted, in the future, boasting of their military support, India may claim the ownership of the War as India’s military intervention was necessary if not essential to win Bangladesh’s independence.

Ironically, Razzaq’s predicament came true – evidenced by Modiji’s message of 16 December 2024!

Major Rafiqul Islam – a decorated freedom fighter and Sector Commander further illuminates the command relationship. Recalling a Conference held at the Indian I81 Brigade Headquarters on 20 November 1971, Maj Rafique noted: “…The Indian Brigade Commander obtained permission from higher authorities, and it was decided that in extreme emergencies Indian officers could be loaned to command our troops…However, we did not need that help and managed to continue fighting with available officers and JCOs”.16 Such provision to induct Indian officers “on loan” in “extreme emergencies” to Command Bangladesh troops reflects the relationship between the two Forces.

These primary accounts and more suggest that, from the inception, the political and military leadership of PGB was cautious to retain the authority and ownership of the War while receiving India’s military help without the risk of “becoming Bhutan.”

Second, in hindsight, the labeling of the Indian troops as “Supporting Forces” and Bangladesh as the “host” country provided a layer of legitimacy to the Indian intervention. It was necessary (if not essential) for India to portray that their troops were “invited” by the “host” country in a “supporting” role to liberate its people. It bolstered India’s claim that her intervention in the East was not a violation of the non-aggression and self-determination norm to an increasingly impatient international audience.

Indeed, once the war was internationalized, much to India’s consternation, her key allies like Yugoslavia and Egypt, along with 104 states, became critical of Indian troops moving into East Pakistan and voted in favor of an Assembly resolution demanding immediate cease-fire and troops withdrawal.17 To India’s surprise and chagrin, the operative clause of a Polish revised draft resolution tabled at the Security Council – just two days before the Pakistani surrender at Dhaka – also demanded for troops withdrawal and omitted the original reference to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the head of the “lawfully elected representatives of the people.”

The urgency of a swift victory and the immediate withdrawal of Indian troops was palpable in the Council and Assembly discussions. Britain and France, fearing escalation, also impressed upon India to “finish the job as quickly as possible”. Their draft resolution demanded not just an “immediate and durable cease-fire” but also “disengagement leading to withdrawal” of troops. Indeed, the geopolitical consideration impelled the necessity of accelerating the pace of victory, made possible by the successive Soviet vetoes at the Security Council.

Third, as a warring party, the Mukti Bahini was required to adhere to the laws of armed conflict. The demands to comply with the Geneva Conventions intensified with the onset of open hostility. However, the PGB, proclaimed in April 1971, was not a recognized state or signatory of the Convention, and its request to participate in Council discussions was ignored. Seemingly, this situation led to placing the Mukti Bahini under the command of “Supporting” Indian forces. Despite Pakistan’s concerns, this arrangement offered a layer of legitimacy and accountability for the Forces in the eyes of the global community.22

Fourth, despite differing motivations, both forces were fundamentally united in liberating Bangladesh. The Directive required the Mukti Bahini to lead the “final stage of liberation,” securing key cities for political and psychological reasons. The Bangladeshi Forces were tasked

with establishing civil administration in the liberated areas, affirming the authority of Bangladeshi leadership during this conflict. India’s military intervention hastened Bangladesh’s independence but framing the war’s outcome as solely “India’s historic victory” undermines the historical truth.

End Thoughts

In summary, the establishment of Bangladesh is a notable example of state creation driven by an ethnic-linguistic movement during the Cold War. The November Offensive revealed the complexities of an internationalized civil conflict, challenging the PGB to maintain its political

authority over the Liberation War. Consequently, the utility functions of the Operational Directive issued on 22 November, to integrate the Indian Forces into Bangladesh’s Liberation War, were underpinned by the normative obligations.

The PGB crafted the Directive not only to unify both forces for coordinated action but also to provide essential legitimacy in this intricate conflict. The tone and tenor of the Directive attest to the fact that PGB retained the political authority and ownership of the War to ensure that the victory is attributed to Bangladesh. Bangladesh was guided by geopolitical considerations – exemplifying Clausewitz’s maxim that war is an instrument of (geo)politics by other means.