Note: This article is based on a presentation the author made at a conference on “Pakistan at 75” , organized by Pakistan Institute of International Affairs, Karachi (Dec 13-15, 2022)

Pakistan is at a critical juncture. The country owes the current crisis to several intrinsic and extrinsic factors. But external challenges thrive off internal shortcomings – for instance, Pakistan’s foremost challenge, i.e., security threat, is not external but a by-product of the internal loopholes.

The security issue has evolved over the last 20 years, mainly for the better – from branding the terror groups such as Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) to fighting for mere survival because of a direly precarious economic situation – an existential threat. But Pakistan needs more to nip it in the bud.

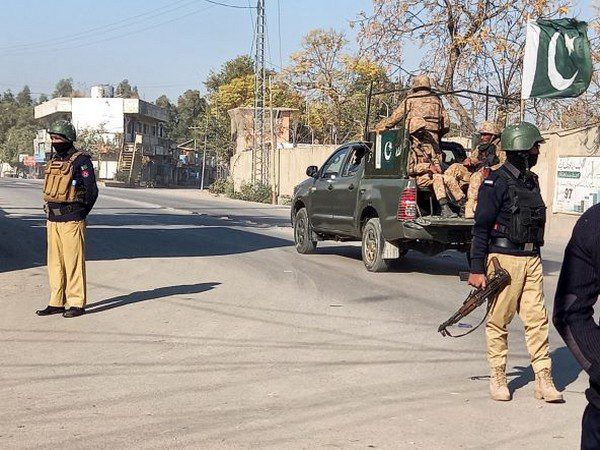

Six deadly attacks in the first two weeks of December – four in Pakistan, one on the Pakistani ambassador in Kabul, and the terrorist raid on a hotel in Kabul on the 12th – underline the external proxy nature of the challenge coming from a volatile Afghanistan, where the current rulers’ host and shelter various brands of terrorists – Al-Qaeda, TTP, Ahrarul Hind, The East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), Jundullah, Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP) and Baloch outfits.

Besides, the emergence of a new Baloch coalition called Baloch Nationalist Army in November 2021 and its close nexus with the TTP further underline the proxy nature of the security challenges that Pakistan is facing today. These terror franchises keep morphing into new entities or alliances to obfuscate the real identity and objective. Even during 2022, these terrorist groups ended up killing nearly 450 security personnel (both military and police) and innocent civilians.

Despite remarkable progress in eradicating terrorism, Pakistan remains caught up in a vicious cycle of proxy terrorism. Though difficult to prove, the sustained nature of recent attacks on security forces in the border regions both in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan, and the targeting of military and para-military personnel through various groups such as TTP, Ahrarul Hind, ISKP, and Baloch insurgent groups in territories adjacent to Iran, reflect a certain pattern.

The additional challenge is the publicly stated opposition to the Chinese interests by some of the Baloch groups and ETIM leaders, which can can also be viewed as a consequence of the mounting US-China rivalry; the American CIA, for instance, announced the creation of the China Mission Center in October 2021 with the avowed objective of containing China’s growing influence across the globe. And Pakistan – with Afghanistan under the control of the militant Taliban is an ideological partner of various terrorist groups such as TTP, ETIM, IMU, Islamic jihad – provides an ideal location for such groups to target both Pakistani and Chinese interests.

The course of events since August 15, 2021, when the Taliban returned to power, also suggests these groups got a new lease of life and shelter all these groups that represent threats to Pakistan, Iran, China, Central Asia, and by extension to Russia.

The previously stated terror outfits have the following commonalities:

A) Pakistan’s armed forces as their common enemy

B) Armed opposition to the Chinese interests

C) Quest for an Islamic caliphate

D) Lip service to the Muslim Umma that they want to unite through armed struggle

E) Rejection of what they call a western-led liberal way of life

F) Cross-border relationships based on a fictional trans-border ideology espoused by Al-Qaeda

G) Role as proxies in global/regional geo-political games

The second most vexing issue is that of governance, which is mainly internal, but being an internal challenge, it amounts to several external problems. The governance void exists due to the following, but not limited to, factors that have helped the ruling elites in externalizing Pakistan’s inherent, systemic problems – scapegoating and deflecting from real issues:

A) Divided power centers – General Headquarters (GHQ), Inters-services Intelligence (ISI), and Prime Minister (PM) office – it is tough to fathom who rules Pakistan.

B) Self-serving, often docile majority of the civil-military bureaucracy with an inclination to corrupt practices for self-enrichment. Best Example: Torkham Border.

C) Mediocrity: As per Peter’s Principal, Pakistan has a highly civil-military conformist, often spineless, bureaucracy

D) Acute imbalance in state revenues and spending has led to astronomical debt – which also poses a security challenge since a weak economy means depletion of state authority and more space to hijack the private actors

E) Extremely poor rule of law – autocracy wrapped in democracy – which has remained helpful to the mighty civil-military elites

F) Undue space for non-state actors: Reliance on and preference for certain religiopolitical, militant groups that can be used for institutional or personal interests

Prime Example:

There is a comprehensive history of supporting and sympathizing with the non-state actors, resorting to politics of expedience, and using private militias and religiopolitical groups in the political power struggles.

Why and how Tehrik-e-Labaik Pakistan (TLP) could get away on two occasions with protests and the seizure of key land communication links? On both occasions, the civilian governments looked helpless and had to give in to some demands.

Such unholy tactics not only undermine the rule of law and the monopoly of power of the state but also encourage non-state actors to take the law in hand as and when they please, which has also harmed our security. When part of the state relies on such groups for political objectives, they automatically create space for non-state actors – for so-called ideological comrades – be they in the urban centers or mosques/madaris run by JUI, Jamaat Islami, Jaish, Lashkar, Ahle Sunnat or similar religious institutions.

They all also serve as shelters and hideouts for all those militants the state of Pakistan legally treats as terrorists. Laal Masjid in Islamabad was a case in point: Several madrassahs in Waziristan, Khyber, and Bajaur are also transit and hiding stations for people wanted on terror charges. But who will dare go after them if their patrons in chief, such as Maulana Fazl ur Rehman and mullahs of his school of thought either in alliance with the military or civilian government?

But medium to long-term damage to the society is immense – at the cost of rule of law, and the credibility of the rulers. Such accommodation has a ripple effect and accelerates the proliferation of radical religious ideologies or even plain religiosity. It encourages and attracts all those elements that tend to define or look at various issues through the religious prism.

So, challenges are both external as well as internal. The external factors prey on the internal faultlines (sectarian, ethnic, sub-nationalistic) such as Baloch insurgencies, and marginal religiopolitical groups that keep disrupting peace and life.

The fight against security and governance challenges requires a clear vision and across-the-board approach for eliminating all those political, ethnic, sectarian, and sub-nationalist fault lines that act as facilitators for external forces inimical to Pakistan. The panacea lies in correcting the 19th-century elitist, exclusionary model of governance. Only then can we effectively address the persisting issues. Without the Rule of Law, respect for it, and adherence to the constitutional roles of each state institution, mitigating and minimizing the externally driven security challenges will remain half-cooked and helter-skelter.