Maria Ali

Muhammad Abdullah

Rosita Armytage is a political anthropologist, policy advisor, and governance specialist working in Pakistan and across Asia.

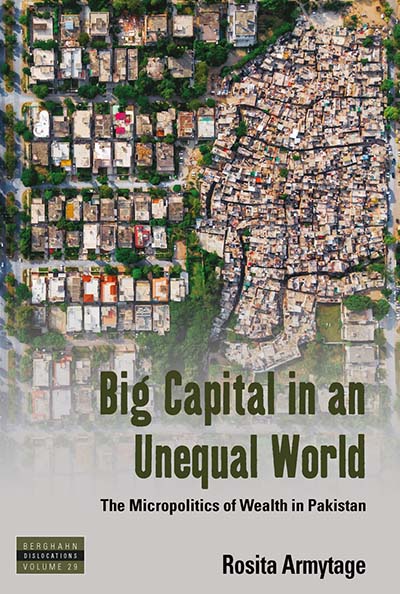

Big Capital in an unequal world is a rich, highly engaging and very insightful biography of Pakistan’s business and industrial elite by Rosita Armytage. It is a long-term field study of the economic and political elite, the “1%” within Pakistani society. This book can be a landmark to understand the classes and structures of Pakistan’s society. It offers insights about power and the numerous multipurpose ways it is accumulated and applied every day in the top 1% in Pakistan. It analyses the networks, social rituals, marriages, and intrigues of Pakistan’s elite. It does so by revealing the everyday, even ordinary, ways in which elites contribute to and influence the modern world’s inequalities. The experience of Pakistan’s wealthiest and most influential elites, operating in a rapidly rising economic environment, contradicts generally held ideas that economic progress leads to increasingly impersonalized and globally uniform economic and political systems.

Armytage spent fourteen months in the field, primarily in the cities of Lahore, Karachi, and Islamabad. The first half of the book sets the stage for the ethnography specifics that follow in the second half. Pakistan is not an easy place to do fieldwork. Armytage starts her book with the methodological issues she faced and how she gained access to these highly isolated, male-dominated settings. All of these issues allowed Armytage to introduce the dynamics of class, gender, and power inside a ‘tribe,’ as well as how they affect elites’ interactions with one another and outside observers. She explored the society not by conducting formal interviews but from inside as an anthropologist.

The author talked about her interactions and experiences with Pakistan’s social elite. She went to high-end parties and weddings. She went to factories and had lengthy conversations over lunch and in cafés. The quotations she collects are frequently remarkable, and they provided us with new perspectives on Pakistan, one of which is– a country holding onto its colonial past while simultaneously breaking free and striking out into the future. Moreover, in the book’s first part, it is disclosed how ‘new money has been created due to the political instabilities in Pakistan. On scrutinizing the book, it can easily be said that the state was in the hands of landlords, industrialists, bureaucrats, and military establishments. A new class of elites emerged in shifting and protecting the insulated interests, including commercial bankers, urban real estate developers, and parliamentarians. Armytage brings together some exciting and insightful themes, such as Navy Raje, a group of new elites that emerged in the late seventies in response to the political and economic instability.

Furthermore, her research focuses on how and why Pakistan’s elite have amassed and kept their wealth, despite, and frequently as a result of, the country’s tremendous political and economic insecurity. Faced with these obstacles, they have developed self-protective networks that have allowed a small number of families to control vast amounts of wealth. They’ve formed inter-familial alliances through carefully chosen marriages, developed close understanding of one another through long-term networking and socializing, and organized a tightly controlled environment of selective inclusion and strict exclusion of those who don’t fit the ‘1%’ social mold.

The middle part of the book gives a notion of the ‘micropolitics’ of elite lives; their personal relationships, everyday lived experiences, and generational histories of Pakistan’s most prominent and wealthy business families. It enables one to learn about that how thoroughly an elite group can mold and control the nation’s economic and political institutions through private networking and parties that take place behind closed doors and define membership in the organization.

Armytage emphasizes the importance of social networks and family in Pakistani business, she also emphasizes how this distinguishes it from the impersonal and quick transactions associated with global finance and capitalism. She also points out that rapidly countries like Pakistan are looking to countries like China for making them their commercial allies, rather than the West, because China’s business model, based on long-term social ties, is far more aligned with Pakistan.

Armytage’s study is a meticulously crafted and nuanced portrait of Pakistan’s elites, enlivened by her extensive ethnographic content, expertly employed to demonstrate broader results. Big Capital in an Unequal World is more than just a boring academic tome. It has both practical and philosophical ramifications. It could compel you to rethink your basic ideas about how capitalism works and what the West’s future holds. If we don’t want to be left behind, I feel the concepts presented in this book are worth considering. As previously stated, this book can be a landmark to understand the classes and structures of Pakistan’s society.

The authors Maria Ali and Muhammad Abdullah are young economists associated with at Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Islamabad.