The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) on Gender Equality by 2030 has seen a halt in progress. Even the countries with the highest gender parity are not on schedule to attain it by 2030. As per the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2022, if current trends continue, gender parity will not be achieved in the next 132 years.

The Global Gender Gap Index published by the World Economic Forum (WEC) tracks progress in four areas: political empowerment, economic empowerment, educational achievement, and health attainment. It offers an action framework for countries to identify core areas requiring time and money to address gender disparity.

The status quo shows that even on global platforms, gender parity is a concept overlooked, rather deliberately forsaken. Only 22 speakers from the 193 member nations in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in September were female. 10 A new UNGA platform was created to address issues of gender inequality, but it only invited these women leaders to debate necessary reform. Similar to this, eight out of the ten pledge partners present at the Global Fund replenishment conference last month were men as if to suggest, “This is where the power sits and this is what it looks like.” As a result of the interaction of gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, religion, and disability, among other variables, hurdles for women from marginalized groups and lower-middle-income countries are exacerbated.

Women in Iran and Afghanistan are at their worst. Afghan women are now even more vulnerable as a result of the closing of numerous safe shelters for victims of domestic violence. Women and girls in Afghanistan remain in increased jeopardy in the wake of the Taliban’s drastic overturning of the prior decade’s modest good progress made toward eradicating systematic discrimination in a matter of weeks in 2021. Girls 12 and older have been prohibited from attending school for more than 14 months, with no signs of improvement, whilst boys were allowed to resume their studies after a brief interruption. The statistics reveal that women’s presence in parliament has decreased from 28% to 0%, their representation in the public service has decreased from 30% to 0%, and the number of girls enrolled in school is now reduced from 4,000,000 to only 1,500,000.

Iran, on the other hand, ranks 143rd out of 146, one of the lowest, on the gender gap index. In economic participation and opportunity, it is placed in 144th position and 142nd in political empowerment. All the statistics indicate an overall desperate situation for the women living under the theocratic regime.

Next is Pakistan – with a population of 107 million, it is ranked 145th on the Global Gender Gap Index, just a rank lower than Afghanistan. The gender gap in the country has been reduced by 56.4% as of 2022. This estimate is by far the highest level it has managed to reach in comparison to previous years. Economic opportunity and participation, which received a score of 0.331 compared to 0.316 in 2021, have seen the highest gains.

Although all countries struggle to meet Gender Equality goals, some are doing a better job than others, and others might want to follow the suit.

For the thirteenth year in a row, Iceland topped the Index. It is the only country to have narrowed the gender gap to 90.8% and is the only one to do so. Gender equality will be attained in Iceland by 2035 if progress continues at this rate. Iceland has eliminated 80.3% of the economic gender gap and is almost at gender parity in both education and health. Iceland was one of the pioneers of legal pay equity in the workplace. However, Iceland stands out in the political empowerment pillar, taking first place for the 13th time in a row in 2022 with a parity score of 87.4%. It is second only to Bangladesh in terms of the number of years it had a female head of state, along with having relatively significant female political representation.

There are some auspicious and astonishing reports from underdeveloped countries too. With a parity score of 81.1%, Rwanda has the highest index position among African nations. Rwanda has eliminated the gender gap in labor force participation through the establishment of childcare facilities and the introduction of maternity leave.

Politically, gender quotas in Rwanda have led to a high presence of women in the legislature and executive branches. In addition, it has improved both health and education.

Nicaragua, the only country from Latin America to make the top 10, has reduced the gender gap by 81%. Nicaragua, which boasts a high percentage of women in politics, has increased its score for political empowerment since 2006 and has achieved parity in both legislative and ministerial seats.

With a score of 80.1%, Germany reentered the top 10 this year. With a female head of state in office for 16 years and 40% of the cabinet, political empowerment for women has steadily increased. Yet, Germany’s progress is unsteady — it has reversed gains multiple times over the years.

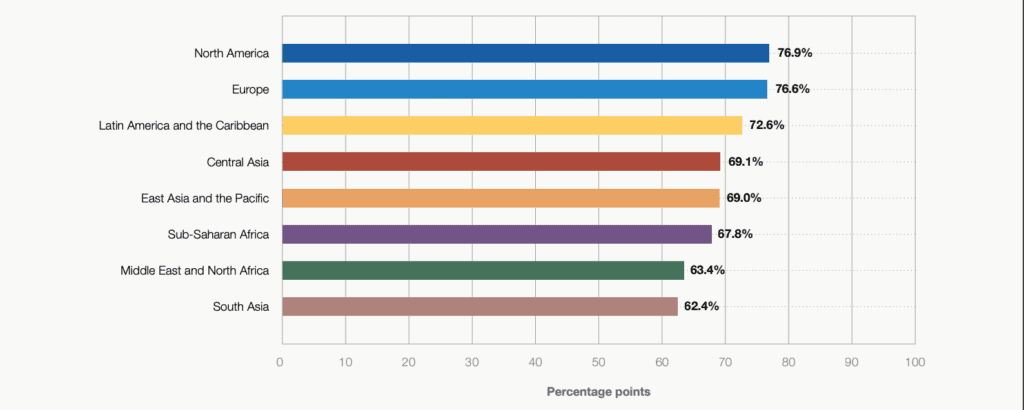

Continent-wise, North America leads the SDG on gender parity, closely followed by Europe.

The total gender parity score increased from 67.9% to 68.1% when comparing this year’s findings to those from last year by looking at the 145 nations included in both the 2021 and 2022 editions. In addition, the Health and Survival subindex grew from 95.7% to 95.8%, and the Economic Participation and Opportunity subindex rose from 58.7% to 60.3%. Political Empowerment stayed constant at 22% while the subindex for educational attainment decreased from 95.2% to 94.4%.

Increased representation of women in political leadership typically results in decisions that reflect larger segments of the community and have a strong role model effect. Data from the Global Gender Gap Index illustrates the advancement of women in public office leadership. The countries with the longest-serving female heads of state include Germany (16.1), Iceland (16 years), Dominica (14.9 years), and Ireland (14 years). Between 2006 and 2022, the average percentage of women in ministerial positions worldwide increased from 9.9% to 16.1%. Comparably, the average percentage of women in parliament increased globally from 14.9% to 22.9%.

The statistics speak for themselves: the countries where gender parity increased in one way or the other, infrastructure, overall quality of life, and community standards ameliorated. From politics and the economy to healthcare and household sustenance, the reduced gender gap can prove efficient for countries. Representatives of countries placed lowest on the scale must realize that progress on gender equality has nothing to do with more resources or capital. Foremost, it depends on sound policies and their effective implementation. It is high time for countries like Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, etc., to address the SDG on gender parity so women can play a better, instrumental role in the countries’ economy, politics, governance, and community development.