It is false to say that there is no democracy in the Muslim world. At least 1.8 billion people around the world, including those in Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Europe, North America, Iran, Iraq, and most other Middle-Eastern countries, practice Islam. Mullahs have rarely ever been in positions of power, except for the Taliban in Afghanistan and Khomeinis in Iran. Political power has been held by secular political elites since the introduction of Islam 1500 years ago. Turmoil is a constant in most Muslim countries, but despite all the social and political turpitudes, the majority of Muslim countries strive and aim for democracy.

In the majority of Muslim countries, democratization is still a difficult task. The reasons why so many Muslim nations lack democracy are more related to historical, political, cultural, and economic causes than to theological considerations. There is a popular notion that in many Muslim countries, the essence of democracy is not enjoyed to the core as the majority lacks freedom of expression and religion.

Many infer that a predominant Islamic code of life hinders an individual’s experience of living a true, democratic life. In forging the Medina Compact, Prophet Muhammad exhibited a democratic spirit in stark contrast to the authoritarian tendencies of many of those who claim to be his modern-day imitators. Although he sought the approval of everyone who would be impacted by its execution, he decided to draught a constitution that was historically particular and founded on the eternal and transcendent truths that had been revealed to him.

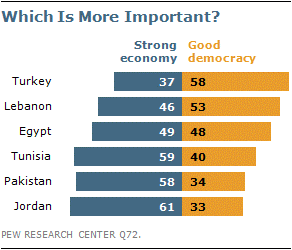

The nexus of Islamic rules and democratic ideals is a paradox, and might as well be understood by looking at the state of democracies in the Muslim world. As per a study conducted by PEW Research Center, a DC-based think tank, In Arab and other Muslim-majority countries, there is still a strong desire for democracy more than a year after the Arab Spring’s early stirrings. Democracy is regarded as the ideal form of governance by substantial majorities in Pakistan, Lebanon, Turkey, Egypt, Tunisia, and Jordan.

The notion that there is no democracy in the Muslim world is untrue. Islam is practiced by at least 1.8 billion people worldwide, including in Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan Europe, North America, Iran, Iraq, and the majority of other Middle-Eastern countries. Furthermore, there is not much historical evidence that mullahs have ever held political authority. Iran, which has been an outlier since the 1979 revolution, and the Taliban in Afghanistan are the other two. Since the arrival of Islam 1500 years ago, secular political elites have dominated politics.

Democracy is seen as the ideal form of governance by large majorities in Jordan, Egypt, Tunisia, Lebanon, Turkey, and Pakistan. These populations favor democracy in its broadest sense as well as its more specific components, such as free speech and competitive elections. Many people in important Muslim nations want Islam to play a significant role in politics. On how much the Islamic legal system should be based, there are, nonetheless, big disputes.

Looking into the archives, Azerbaijan appears as the first ever secular Muslim democracy. On May 28, 1918, the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was founded. This was a momentous historical occasion. With a statute issued in July 1919, it became the first majority-Muslim country to offer women the right to vote and to run for office, making it the first secular and parliamentary republic in the Muslim world. However, in a series of unfortunate events, it was invaded by the Soviet Red Army on April 28, 1920, and the newly-established secular Muslim democracy collapsed.

Azerbaijan regained its independence from the USSR in 1991, one hundred years later. It is now the region’s largest economy, implementing significant international energy and transportation projects like the recently launched railroad linking Asia with Europe or significantly enhancing the energy security of European countries. Most importantly, Azerbaijan is actively working to advance these ideals throughout the region and beyond based on its own experience with multiculturalism and interfaith acceptance, where Shia and Sunni Muslims, Christians, Jews, and others continue to live in peace and respect.

Like other developing nations, the majority of Muslim nations are passionately driven by fundamental needs and a desire for modernization, development, and dignity. Their idea of a brighter future has been rooted in a straightforward version of a strong central state with a top-down reform strategy for the previous few decades. The democratic system, which offered a complex, multi-institutional participatory structure rooted in individualism and liberal principles, was judged to be less likely to succeed than that vision. Strong secular nations’ inability to satisfy the growing needs of newly educated populations drove many to look for alternatives. Social and political groups were conscious of the influence of religion in swaying public opinion after the Iranian revolution of 1979.

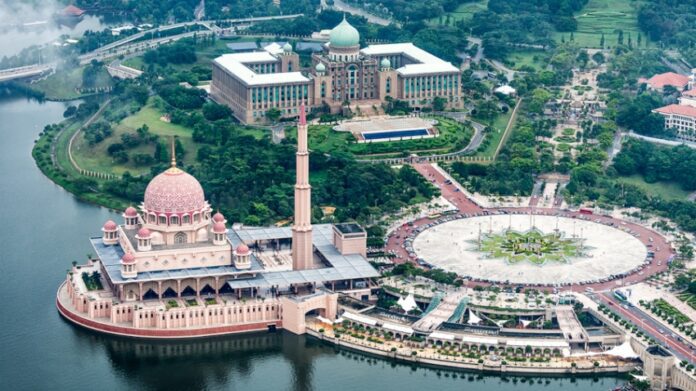

But there is an exception that stands out: Malaysia. Malaysia runs on parliamentary democracy and has enjoyed a stable political and economic climate for decades. The rule of law prevails and it is not in the interests of the government or private sector leaders to allow any disruption to the generally peaceful atmosphere that the country enjoys. Malaysia has had a good record of maintaining law and stability and is one of the safest countries to live and work in this part of the world. The nation enjoys a harmonious social, political and economic environment that has contributed to strong economic growth.

There are not many examples of successful parliamentary democracies, because turmoil tends to stay constant at the heart of each Muslim state (or, most of them).

Islam is still brought into the debate as a weapon that may be used by both the ruling party and the opposition, by modernists and traditionalists, and by organizations on the left or right of the political spectrum. Islam is owned, interpreted, and utilized by everyone. Although different Islamic groups disagree on their preferences for democracy or dictatorship, they all favor Islam above secularism.

But, the disagreement of the clergy with the secular or liberal-minded and vice versa has also led often to better advocacy and activism for more agency and freedom of choice. Countries such as Pakistan could be seen as an example of that.

Pakistan is transitioning to a democratic government after decades of military control. Provinces in the nation currently enjoy greater autonomy and smooth political transitions following the 2013 and 2018 elections. Parliaments, including the Senate, National, and Provincial Assemblies, have become important institutions. Despite political unrest and other concerns, all political parties and governmental organizations concur that the roles of the federal and provincial legislatures should be expanded. However, the country barely managed to skip governance and democratic void after the ouster of Imran Khan, the former PM, on April 10, 2022.

But, despite the perils of poor governance, lack of livelihood opportunities, and dynastic politics, a majority of Pakistanis prefer democracy.

In a 2012 study conducted by PEW Research Center, a plurality of Pakistanis and majorities in five of the six countries surveyed agreed that democracy is the best type of government. Additionally, these countries have a strong desire for particular democratic institutions and rights like free speech and competitive multi-party elections. Other objectives are as significant. Many people believe that economic development and political stability are vital priorities. Turkey and Lebanon are the only two nations where more than half of respondents say that a robust economy is more important than a good democracy. The majority of Tunisians, Pakistanis, and Jordanians prioritize the economy, while Egyptians are divided.

But, as of now, a lot is changing in the Muslim world. The political situation is dominated by internal power conflicts. In the Muslim world, political issues rather than issues of religion or theology pose the biggest risks to human rights. It has been questioned whether Muslims will be unable to maintain control over their economy, political systems, and cultural resources in a world that is becoming more globalized.

Though Turkey stands out as a major exception, opinions on the economic situation in these nations are generally pessimistic. Nearly six out of ten Turks (57%) believe that the economy of their country is doing well, but at least seven or more out of ten people in Pakistan, Lebanon, Tunisia, Egypt, and Jordan disagree.

However, a lot of people in the Muslim world see optimism in such a globalizing society. The press, academics, Islamic reformers, and the youth all see enormous prospects, especially if they join the global civil society. The key issue is how to implement new concepts and procedures in a manner that the structures sustain and persevere. Another food for thought for the leaders of the Muslim world is that dysfunctional, corrupt, repressive states are never capable of reform. Apathy and despair breed radicalism and a battered global visage. Can they afford all that in the present-day world that is highly polarized and runs on the principles of realism?